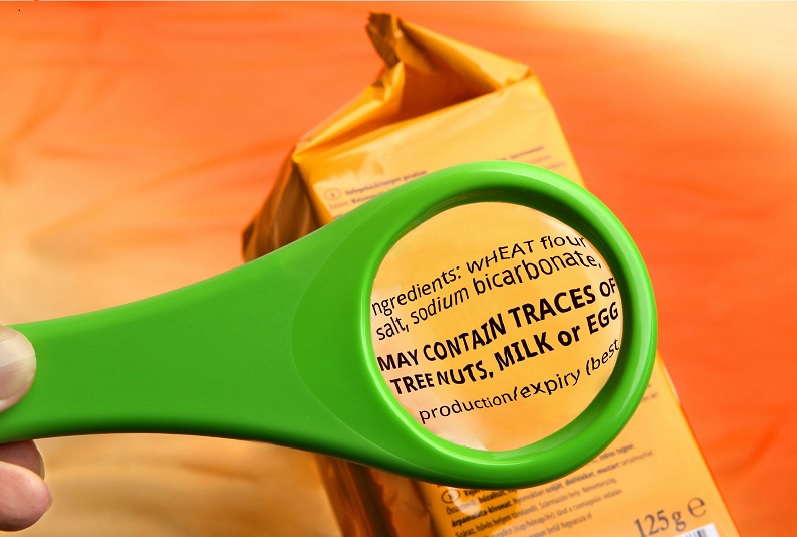

If there’s one thing everyone does every day, it’s eating and, except for some fresh produce, most of our food comes from a package. The industry uses packaging to store, transport and preserve food. That said, let us look at the labels on these packages. What do they tell us? Do you pay enough attention to what they say? It is vital to know that, as consumers, we have the right to know what we are buying when we choose food, and we should have as much information as possible at our fingertips.

In this article, we will analyse these aspects that seem very rudimentary, although we do not give them as much importance as we should.

HOW DOES LABELLING INFLUENCE OUR FOOD CHOICES?

The scientists Gustavo Schneider and Anastasiya P. Ghosh posed the same question in their 2019 study Should we trust front-of-Package Labels? How food and brand categorization influence healthiness perception and preference. Using the scientific method, the study examined how front-of-package nutrition labels (FoPNLs) influenced consumers’ preferences in making healthier choices, i.e. whether or not they bought and consumed a product based on its labelling.

This study reports that when we go shopping, we ask ourselves whether the food product we have in our hands is healthy or not and answer by looking at the FoPNL. It seems a very reductionist way to do it because, in this case, we fail to consider many other important aspects of the food we will explain later. Also, due to a lack of knowledge or other reasons, there is a general tendency for the population to make mistakes when calculating calories. As a result, we can say that, in general, we allow ourselves to be led astray by this front labelling, thus allowing it to affect our health.

In addition, the study shows there is a predisposition to choose foods with FoPNLs that claim their contents are healthier or have a given nutrient, such as “low fat” or “high fibre” food. Consumers tend to trust a product more because FoPNLs purportedly provide an idea of its healthiness, and they perceive positive health consequences. Therefore, a consumer may believe that a product or brand is healthy (or unhealthy) just because of what the FoPNL states. So, what is the problem? Some -or all?- products are not healthy or are straightforwardly unhealthy and have a strategically misleading front-of-package label that encourages consumers to buy or consume more of that product.

In line with the previous considerations, we find Brownell and Koplan’s (2011) study Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling — An Abuse of Trust by the Food Industry?, which explains that in January 2011, two weighty food industry trade associations -Grocery Manufacturers of America (GMA) and the Food Marketing Institute- announced an innovative and voluntary approach to nutrition labelling under the Nutrition Keys programme that sought to standardise FoPNLs on food products to provide objective nutrition information to consumers.

So far, so good. But there is a catch: this programme perpetuates the competitive and outdated food industry model, promoted without considering what the US government and the public health community might have to say. In addition, the symbols used can deliberately mislead consumers because the nutrients listed on the FoPNLs can change at the company’s discretion. A product perceived as suitable and healthy due to its high presence of optional nutrients (potassium, vitamins, calcium or iron) should not be considered so due to the excessive content of required components (sugar, sodium, calories or saturated fat).

On the other hand, Brownell and Kaplan (2011) discuss the traffic light system, which uses green, yellow or red figures for each nutritional component of a food product, thus indicating whether it is healthy, average or unhealthy respectively. This system is very controversial because it allows manipulation: it has no solid scientific basis, and the consumer, who only looks at the packet for an average of thirty seconds in the supermarket, may end up buying unhealthy products. Finally, it is known that the food industry spent up to 1.5 billion dollars to press the European Union to approve and use this traffic light system.

SUMMING UP

In conclusion, we make the following observations:

- We find ourselves in a scenario where diabetes, obesity, strokes or hypertension are becoming more prevalent in the population, largely because of poor eating habits.

- We need FoPNLs to allow consumers a quick and easy overview of nutritional value and risks associated with each food product. The traffic light option would be an adequate tool to make a relative assessment and could promote more informed decision-making, provided there is scientific evidence supporting it.

- Labelling is important because it is the first stepping stone for building a sustainable and healthy food system. So while consumers must receive help to make better nutritional choices, we should also demand proper labelling. It is and must be a crucial issue for policymakers and retailers.

- Evaluations of front-of-pack labelling alternatives are currently underway. Evaluations of front-of-pack labelling alternatives are currently underway. However, it is a controversial issue, so we must wait to see what the future holds.

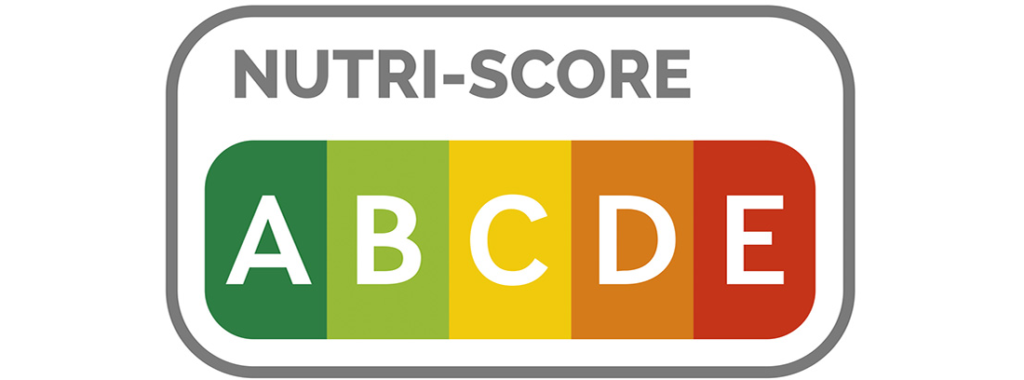

In the Spanish state, providing information on food composition and nutritional value has been mandatory since 2016. Yet, the French labelling system Nutri-Score was implemented only in early 2021. It classifies a food product on a scale from A to E (from the healthiest to the least healthy) using colours from green, passing through yellow, orange to red.

Source: Meat Entepreneurs Association – ANAFRIC.

What is the problem? The classification works based on an algorithm that considers favourable and unfavourable amounts of nutrients. This is why it is so easy to mislead and why many associations and groups linked to nutrition and dietetics criticise it. A much-talked-about example was the case of olive oil. Although it is a very healthy food typical of our Mediterranean diet, it receives a very negative classification in this Nutri-Score system because oil is 100% fat and, therefore, has no “positive values” to compensate for the result.

Unfortunately, there is still no agreement on a FoPNL system, and as the cited studies report, producers end up regulating themselves with their own labelling systems.

THE ART OF READING FRONT-OF-PACKAGE NUTRITION LABELS

As the Catalan Food Safety Agency points out, labelling is the principal means of communication between producers and consumers. It allows us to know the food: its origin, its preservation procedure, the ingredients it contains and the nutrients it provides to our diet.

A label, thus, contains information about a food product, mainly its nutritional data (energy or caloric value; fat, saturated fat, carbohydrate, protein, and salt content). This information may appear in different ways: indications, drawings, signs or mentions found on the packaging, FoPNLs, bands or any other element accompanying a food product.

Quina informació és obligatòria en una etiqueta d’aliments envasats?

What information is mandatory on a label for packaged food?

- If the packet has a capacity of less than 25 cm², the nutrition information is not mandatory.

- If the packet capacity is less than 10 cm², the label is required to include neither the nutrition information nor the list of ingredients.

- The label must always include the name of the food, the presence of possible allergens, the net amount, and the date of minimum durability, irrespective of the size of the package.

- Additional information is mandatory for packaged foods containing specific gases, sweeteners, glycyrrhetinic acid (or its ammonium salt), high amounts of caffeine, phytosterols and finally, frozen meat or meat preparations and frozen unprocessed fishery products.

Nutritional information allows us to know the nutritional value of food and determine the number of calories and nutrients in a serving. It also allows us to compare the nutritional value of a food with others and to choose those foods that contribute to a healthy diet according to our needs.

Besides the nutritional information on food labels, there are other significant elements:

- Name of the food

- Date of minimum durability or use-by-date

- Special storage or use conditions

- Name or business name and address of the food business operator

- Country of origin or place of provenance

- Indication of the lot following Royal Decree 1808/1991 of 13 December 1991, which regulates the instructions or marks that allow the identification of the lot.

- The labelling must be in the official language of the State.

HOW DO I INTERPRET NUTRITIONAL INFORMATION IN A FoPNL?

Labels always express nutritional information per 100 grams or 100 millilitres of product, and this reference allows us to compare the nutritional value of different foods. More specifically, such nutritional information indicates:

- Energy value: the amount of energy in the food, expressed in kilojoules (kJ) and kilocalories (kcal).

- Each nutrient’s contents, in grams (g): fats, saturated fats, carbohydrates, sugars, proteins, and salts.

- Optionally, the amounts of monounsaturated fats, polyunsaturated fats, polyalcohols, starch, dietary fibre, vitamins, and minerals.

- Optionally, nutritional information may appear as per portion or consumption unit. In this case, the label must indicate portions or units size and numbers in the package; for example, 125 g yoghurt or 20 g portion.

- Optionally, labels may exhibit the reference intake (RI), i.e. the recommended daily amounts of energy and different nutrients for an average adult, as shown below:

| ENERGY VALUE O NUTRIENT | REFERENCE INTAKE |

| Energy value | 8.400 kJ / 2.000 kcal |

| Total fat | 70g |

| Saturated fat | 20g |

| Carbohydrates | 260g |

| Sugars | 90g |

| Proteins | 50g |

| Salt | 6g |

Veiem a la part inferior un exemple d’etiqueta extreta d’un formatge comprat a un supermercat. Comprova si entens tota la informació que hi diu amb el que hem explicat.

Below is an example of a front-of-package nutrition label taken from a cheese bought in a supermarket. Check if, with what we have explained, you understand all the information it says.

LABELS, TECHNOLOGY AND FOOD WITH NAME AND SURNAME

Actualment tenim a l’abast moltes eines tecnològiques que ens proporcionen informació i evidentment, la indústria alimentaria hi és present. En aquesta línia hi destaquen les aplicacions que permeten obtenir informació interessant i útil al consumidor a partir de l’escaneig dels productes. En el següent enllaç es mostra un recull de fins a nou aplicacions diferents. És però important que no hi dipositem la nostra absoluta confiança en aquestes eines i les fem servir com un suport, atès que han sigut ideades amb diferents dades i podríem trobar que diferents eines indiquen resultats diferents per a un mateix producte. Per aquests motius, cal recordar que és imprescindible que llegim sempre les etiquetes i traiem les nostres pròpies conclusions.

We currently have many technological tools that provide information and, as expected, the food industry is present. In this context, software applications that allow consumers to obtain interesting and useful information by scanning products stand out. Here is a compilation of four different nutrition label scanning applications. It is crucial that we do not place our absolute trust in these tools and use them as a support, given that they have been devised on the ground of varied data. Therefore, we might find that different apps provide different results for the same product. For these reasons, we must remember that it is imperative that we always read the FoPNLs and draw our conclusions.

Per acabar, remarcar que hi ha disponible una eina informàtica europea sobre l’etiquetatge dels aliments que s’anomena FLIS (Food Labelling Information System) que permet als usuaris seleccionar un aliment i recuperar automàticament les indicacions obligatòries d’etiquetatge de la Unió Europea. Es cobreixen un total de 87 categories diferents d’aliments i a més, s’hi poden consultar les disposicions legals pertinents i documents d’orientació existent.

Finally, it should be noted that the European food labelling software tool called FLIS (Food Labelling Information System) allows users to select a food and automatically retrieve the mandatory EU labelling indications. FLIS covers 87 different food categories. Users can also consult relevant legal provisions and existing guidance documents. The main objective of this tool is to help food business operators to identify the mandatory labelling indications that should appear on their products to promote the correct implementation of the relevant legislation by food businesses and to facilitate the task of national control authorities as well as to provide information to consumers to make informed food choices.